“Car biz is hell” Tesla CEO Elon Musk recently said in a twitter exchange. Media eagerly reported that the electric car pioneer is sleeping at Tesla’s factory, to remedy production delays on its latest model.

But production delays are just that…production delays. They are, at worst, a minor bump for the electric turn in how we propel ourselves about. Yes, electromobility is gaining political momentum in Europe. This amidst the never-ending dieselgate scandal, competitive pressure from China, and Europeans’ growing awareness of climate change and the health effects of air pollution.

Discussions on electric cars often centre, and rightly so, on the practicalities regarding the roll-out of charging systems. Consumer groups have often pointed to the savings consumers can make if the transition to electric, and other low carbon, cars is spurred. But we should also ask the question: What does the electrification of cars mean for our very energy system?

Electrification and the EU’s energy policy

Electrification is increasingly considered a way to clean up air pollution and mitigate the climate effects of road transport [1]. This comes at a time when the EU is redesigning its energy policy, aspiring to become a global champion in renewables and to offer more innovative electricity services to consumers.

Adding electric cars increases pressure on the grid. At the same time, electricity increasingly comes from variable sources such as the wind or sun. But not all consumers will be able to charge their car at midday when the sun shines the most. Making consumption flexible can relieve the grid, and support the shift to renewables.

Cutting edge technology makes it possible to choose the right time to charge our car or use its battery to store energy. The benefits of transport electrification can therefore be extended to the energy system as a whole, as the renewable energy in our grid is used more flexibly. In parallel, batteries of electric cars, when not in use, are a storage facility that can help match renewable electricity production and demand.

If Europe is serious about becoming a near zero-carbon society by 2050, 2030 should already look very different than today in terms of how we power our lives and move about. For consumers there are two important elements here: the product offer and the energy offer.

Create an attractive product offer for consumers

I t all starts with availability. In most European countries, the market share of electric vehicles is very close to zero. This can easily be explained by the industrial and commercial strategies of car manufacturers. Despite very ambitious claims made by industry, the reality is that European consumers have very limited choice when it comes to electric vehicles.

t all starts with availability. In most European countries, the market share of electric vehicles is very close to zero. This can easily be explained by the industrial and commercial strategies of car manufacturers. Despite very ambitious claims made by industry, the reality is that European consumers have very limited choice when it comes to electric vehicles.

There are only around 20 battery electric models available on the market, compared to more than 400 diesel and petrol engines. Current sales practices also mean that electric cars are often not displayed in showrooms, making it difficult for consumers to opt for them. To accelerate the transition, car makers and dealerships must finally provide more electric choice to consumers. The EU could give the right push by, for instance, requiring that manufacturers put a minimum number of electrified vehicles on the market.

This transition should be affordable to consumers and generate savings. The price of electric cars is already dropping. Sometime in the early 2020s, consumers will probably save money as lower maintenance and running costs will make electric models more attractive than diesel and petrol ones.

Energy markets ought to mirror innovation in the transport sector…

Owning an electric car could become even more affordable if the energy market mirrors developments in the transport sector. This is needed as electrification radically alters the supply/demand system of the energy market.

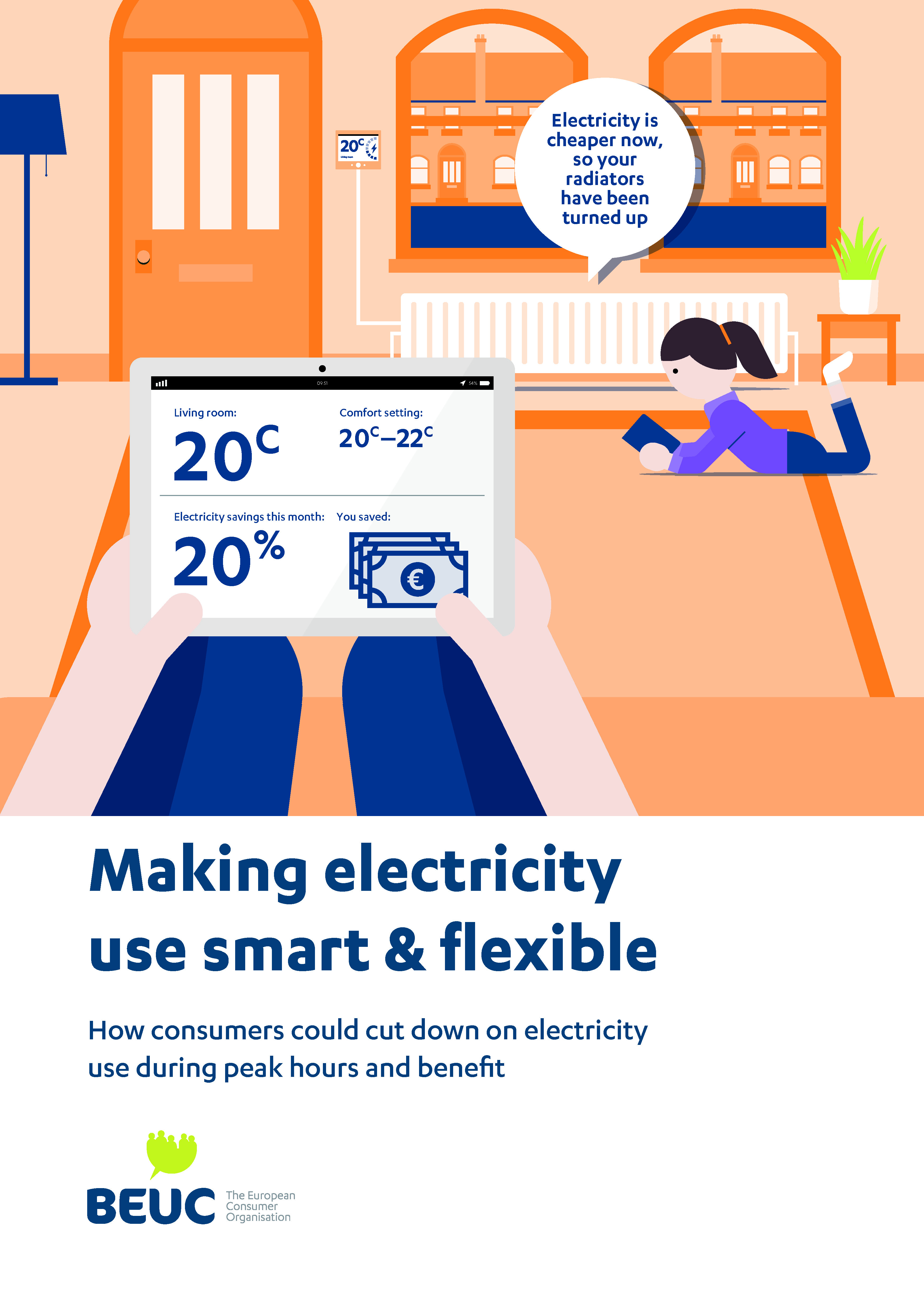

Quite simply: adding electric cars increases pressure on the grid. At the same time, electricity increasingly comes from variable sources such as the wind or sun. But not all consumers will be able to charge their car at midday when the sun shines the most. Making consumption flexible can relieve the grid, and support the shift to renewables [2].

The benefits of transport electrification can therefore be extended to the energy system as a whole, as the renewable energy in our grid is used more flexibly. In parallel, batteries of electric cars, when not in use, are a storage facility that can help match renewable electricity production and demand.

For example, consumers could get more favourable prices if they charge their car when solar panels and wind turbines are running at full speed. Or perhaps they could offer their battery for energy storage when their car is not in use. Research shows that such schemes could save consumers in UK and France up to 650 EUR/year per car net by 2030. And while many would argue that our power grids will need expensive upgrades to handle so many electric cars, these flexible consumption schemes are expected to reduce the need for such upgrades. They could thus spare consumers additional costs.

…but only with consumers on board

So the EU’s energy policy needs to be prepped for the supply/demand shake-up brought by the electric car. How does this play out when consumers want to charge their car?

Choosing the most economic petrol station to fill up a car requires only a quick glimpse on the fuel price board. Choosing the most advantageous flexible charging offer will require some extra effort.

Choosing the most economic petrol station to fill up a car requires only a quick glimpse on the fuel price board. Choosing the most advantageous flexible charging offer will require some extra effort.

In fact, consumers will need to pick up an electricity offer for their car, just as they do for their home. To make sense of how much they can save by charging when prices are low, they will need to factor in their transport habits and needs. They could then decide if they want to benefit from fluctuating prices – depending on the pressure on the grid and the yield from renewable sources. Here, the idea of flexibility, and having more offers that provide it, is only the starting point.

Unlocking the full range of benefits of electric vehicles for consumers requires more than just providing this option a such, of course. Real innovation must tick consumers’ boxes for simplicity and transparency, so they can find the best deal (whether flexible or fixed). Looking at current energy markets, with their jungle of electricity offers, we see that competition does not achieve this. Which is why policy makers should set the tone with the ongoing redesign of energy markets and ensure that new offers are designed around a set of consumer principles.

With the ongoing revision of energy and transport policies, the EU has a once in a decade opportunity to establish a mutually beneficial relationship between the energy and transport sectors. If policy makers take up the glove, they can provide Europeans at once with affordable electric cars, innovative electricity services, cleaner air and higher chances of winning the fight against climate change.

[1] See Transport & Environment (2017) Electric cars emit less CO2 over their lifetime than diesels even when powered with dirtiest electricity.

[2] This works through aggregators. These are types of energy companies that can set up an agreement with several consumers. Aggregators can temporarily reduce or increase consumers’ electricity consumption depending on the overall supply and demand. They can also operate on behalf of a group of consumers, who engage in self-generation by selling their excess electricity.