We live in an increasingly busy world with many demands on our time. One place where we generally don’t want to linger any more than is necessary is the supermarket. At the same time, when consumers go shopping they are increasingly concerned about the healthiness of the food they buy. (Not surprising amidst shockingly high levels of obesity and overweight across Europe.) One way to better inform consumers about the nutritional quality of foods and beverages and help them spend the time in supermarkets more wisely is by improving nutritional labelling.

Today, (and thanks to EU law) consumers can find on the pack the amounts of key nutrients such as protein or sugar given per 100g of the product. However, this information is usually on the back of the pack, in very small font and crucially isn’t that easy to use for the average consumer. Indeed, without a high level of nutritional knowledge how are you expected to know if 8.6g of saturated fat or 7.6g of sugar for example is high or not?

In other words, at the moment it is generally left up to the consumer to make these assessments (in the busy supermarket environment) but lacking a high level of nutritional knowledge, many can end up lost in confusion when trying to make a healthier choice.

This is why we have consistently called for additional colour-coded front-of-pack nutritional labelling schemes to help make the healthier choice the easier choice for consumers. Logical colour-codes placed on the front-of-pack help shoppers to assess the nutritional quality of products at-a-glance without having to scour the package for info.

Issue Starting to Simmer

Front-of-pack nutritional labels have become somewhat of a hot topic recently with many developments, (some good, some bad), taking place in Europe.

Although EU food labelling legislation brought in important new improvements for consumers in 2011 [1], policy makers unfortunately failed to introduce EU-wide mandatory colour-coded front-of-pack nutritional labels. They did, however, leave the door open for Member States to establish such schemes in their own countries (albeit on a voluntary basis).

Colour codes are a vital component of a simplified nutrition label but it is essential that the colours are appropriately assigned. To allow consumers to gain an accurate picture of a given food or drink’s nutritional quality, colour-coding needs to be established on a uniform basis e.g. 100g of product.

Until recently, only the UK had made the most of this opportunity by formally endorsing the ‘traffic light’ label for food and drink companies in 2013. This label provides information on 4 key nutrients of concern (fat, saturated fats, sugar and salt) and gives a red, amber or green colour for each nutrient depending on the amounts.

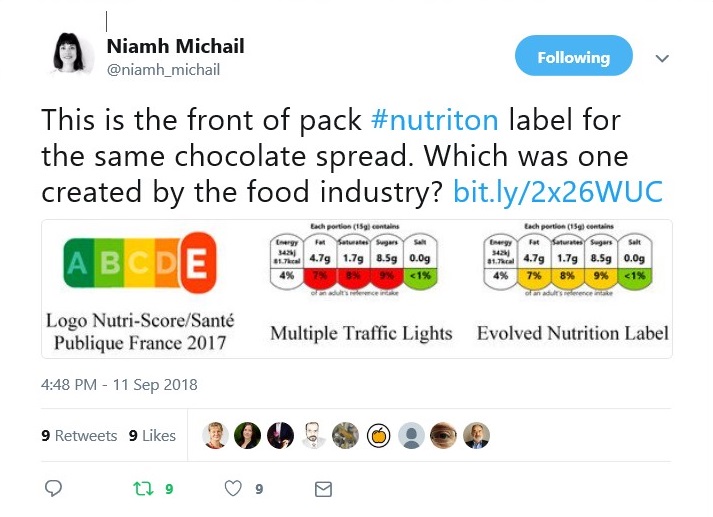

France, in 2017, was the second country to recommend a colour-coded front-of-pack label. After a considerable amount of research, France decided that NutriScore was the best system for French consumers. This scheme still uses colours to help consumers but differing from the UK traffic light system, it instead provides an overall ‘score’ for the product from A (dark green) to E (dark orange). The calculation for the score is based on both positive (such as fruit and vegetable content) and negative elements (such as saturated fat or sugar content).

In August this year, Belgium announced that they were following France’s example and made an official recommendation for the use of NutriScore.

In the absence of action for an EU-wide mandatory colour-coded label, it’s a welcome sign that Member States are taking matters in to their own hands to help improve the diets of their citizens.

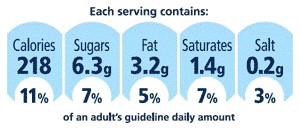

However, the food and beverage industry by and large remain vigorously opposed to these consumer-friendly schemes. Instead, they continue to push the use of a single-coloured portion-based system known as ‘Reference Intakes’. This system shows how much energy and nutrients of concern are present in a portion of a food or beverage and what each portion represents as a % of an average person’s daily reference intake.

Unfortunately, consumers find this model difficult to understand and French researchers recently found that it came bottom of the class for its impact on the nutritional quality of shoppers’ baskets.

At the same time, certain food and beverage companies, who vigorously opposed colour-coding a decade ago, are now promoting a colour-coded scheme they have devised themselves. The ‘Evolved Nutrition Label’ (ENL) is the creation of 5 multinational food and drink companies: Coca Cola, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Unilever and Mondelez.

The ENL allows ‘smaller portions’ to use more lenient criteria to determine the colours. What this means in practice is that even very high-fat, high-sugar food products can manage to get an amber instead of a red for these nutrients if the portion (designated by the food company) is small enough. Is this really in the consumer’s interest?

Colour codes are a vital component of a simplified nutrition label but it is essential that the colours are appropriately assigned. To allow consumers to gain an accurate picture of a given food or drink’s nutritional quality, colour-coding needs to be established on a uniform basis e.g. 100g of product.

Is it logical for a chocolate spread comprised of almost 90% fat and sugar to show ‘ambers’ simply because the producer has decided that a portion is only 15g?

Nutrition Labels need to be Fit-for-Purpose

As the attention in nutrition labels surges, it is evermore clear that we need to ensure that these schemes are fit for the purpose they were designed. In other words: does this label actually help consumers to make healthier choices?

While BEUC is in favour of colour-coded front-of-pack nutritional labelling in general, it is important that any such scheme which is developed should be done so in an independent and transparent manner. Furthermore, they should be based on strong scientific evidence which can demonstrate the objective understanding by consumers of the scheme.

Today, (and thanks to EU law) consumers can find on the pack the amounts of key nutrients such as protein or sugar given per 100g of the product. However, this information is usually on the back of the pack, in very small font and crucially isn’t that easy to use for the average consumer. Indeed, without a high level of nutritional knowledge how are you expected to know if 8.6g of saturated fat or 7.6g of sugar for example is high or not?

Given that consumers make purchasing decisions in a matter of seconds, any new nutritional label should, at a minimum, be on the front-of-pack and use rational colour-coding to allow straightforward comparison between products and give an accurate representation of the nutritional quality of a product.

At a time when diet-related diseases are skyrocketing, properly-designed front-of-pack nutrition labels offer an opportunity to help signpost consumers towards healthier choices.

[1] Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers