When EU governments instructed the European Commission in June 2013 to start negotiating a free trade agreement (TTIP) with the United States, they requested provisions on investment protection and Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) be included in the agreement.

Following heavy pressure by civil society groups, the ISDS clause was put to public consultation and (despite the highly technical terminology), more than 100,000 organisations and individuals submitted their feedback before it closed on July 13th.

While consulting the public on the ISDS mechanism is a step in the right direction, efforts to reform the system show how deeply flawed ISDS is. ‘’A system which requires so many patches to be fixed does not work‘’ Rob Weissman, President of ‘Public Citizen’, said at the Transatlantic Consumer Dialogue conference on TTIP.

ISDS originated in the 1950s to allow investors to go to arbitration when they believed a host nation, usually a developing country, had acted unfairly towards their business or expropriated their assets.

In the past few years, the number of ISDS cases has skyrocketed and increasingly it has been used for purposes other than those for which it was created. According to UNCTAD, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, fewer than 50 cases were litigated between the 1950s and 2000, while 568 are known to have occurred as of the end of 2013. There are many examples of large firms instigating claims against governments (thereby hitting taxpayers’ resources) seeking multi-million or billion dollar payouts over public health, consumer and environmental policies which allegedly impair their investors’ rights.

A notorious example of that is Philip Morris Asia attacking Australia’s plain packaging rules for cigarettes, which had been previously upheld by the Australian Supreme Court.

As demonstrated in the recent Transatlantic Consumer Dialogue conference on TTIP, held in Washington in late June, (read the conference report), civil society on both sides of the Atlantic remains unconvinced of the need to include the ISDS mechanism in a transatlantic trade deal.

Moreover, the proposed changes to the ISDS mechanism put forward by the Commission far from allay our concerns. Let me give you 3 examples:

- Definition of investor: It is essential to foreclose the possibility of firms’ ‘national planning’ such as the use of offshore subsidiaries or the setting up of shell companies with the intent of challenging governmental policies. Requiring – as the Commission does – that the claimant holds ‘substantial business activities’ in the host country is a positive improvement. However, a more precise definition of what ‘substantial’ means is needed and denial of benefit provisions must be reinforced ensuring that firms have substantial business activities also in the home country. In both cases, the burden of proof should be borne by the claimants and not the respondent state.

- Frivolous claims: The attempts of reducing such claims by out-ruling those “manifestly without legal merit” or “unfounded as a matter of law” will remain vain as long as the definition of the two categories is not specified and the array of substantive rights granted under Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral Investment Treaties to investors remains broad as it is currently the case.

- Qualification of arbitrators: The Commission rightly proposes that arbitrators shall not be affiliated with or take instructions from any disputing party or the government of a party with regard to trade and investment matters but these limitations should be extended also to past activities and matters not related to trade, as well as paired by an effective and impartial mechanism to remove arbitrators when conflicts of interests are present.

More resolute action than reforming something which is inherently flawed is needed and possible.

When asked about it, EU’s negotiators say the Commission is bound by the negotiating mandate, citing the aforementioned request for provisions on investment protection and ISDS.

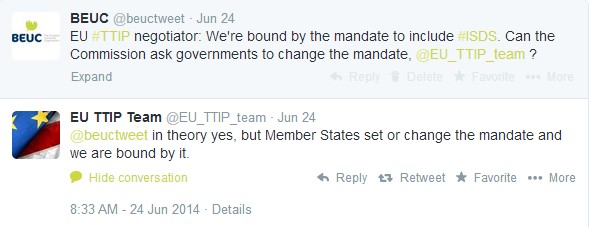

However, the Commission has the competence to ask for the exclusion of ISDS from TTIP. This has been confirmed by the EU TTIP negotiation team itself on Twitter, after BEUC inquired about the subject.

It is clearly in the Commission’s task to show real leadership and listen to public concerns.

While BEUC recognises foreign investors’ right of access to justice where host states behave unlawfully, we do not see the necessity to have a special Investor-State Dispute Settlement mechanism in TTIP. The reason is clear: both the EU and US court systems are adequately equipped to address such cases effectively and efficiently.

A TTIP deal serving the public interest would strike the right balance between protecting investors and safeguarding the EU’s right and ability to regulate according to the public interest. ISDS does absolutely not form part of such an agenda.